City plans to hold hearings on the issue over the next year

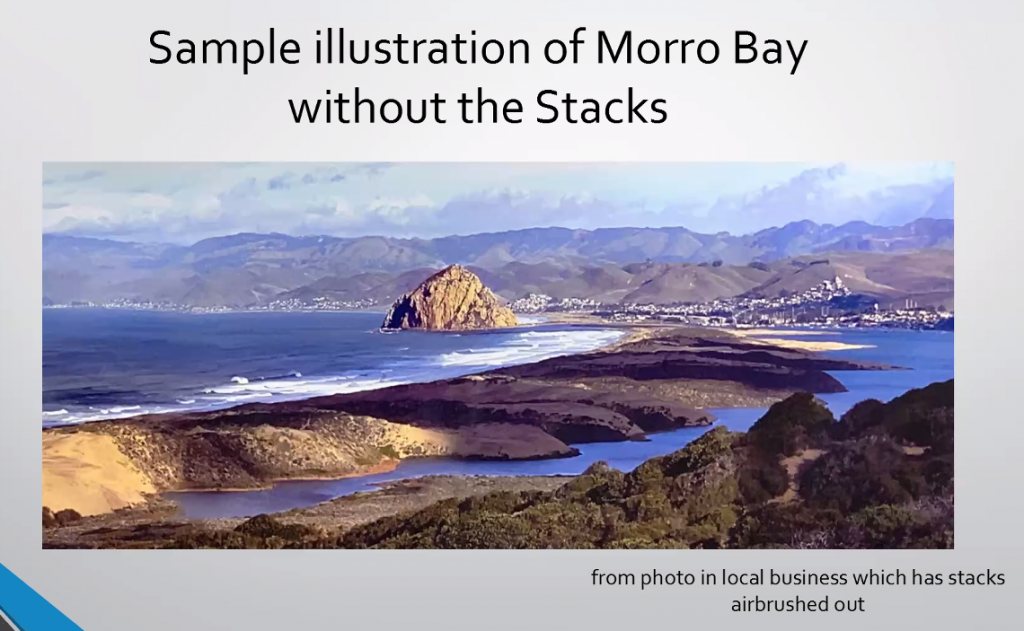

MORRO BAY — It’s a question that Shakespeare might pose—Are the power plant smokestacks to be or not to be—left standing, that is.

The future of Morro Bay’s iconic smokestacks became a little clearer on Sept. 8 after an online meeting with government and power plant officials.

The Zoom meeting, moderated by Don Maruska, eventually had over 200 people tuned in to hear the pros and cons of the “stacks” remaining or being taken down by power plant owner Vistra.

On hand were Vistra Senior Vice-President for Corporate Development and Strategy, Claudia Morrow and Vistra’s Director of Decommissioning and Demolition, Dianna Tickner; Tim Fuhs, compliance supervisor with the County Air Pollution Control District; and John Bystra with the State Department of Toxic Substance Control.

The issue of the stacks arose in June when Vistra declared its intentions to tear down the power plant as part of its “Battery Energy Storage System” (BESS) project, a 600-megawatt capacity massive undertaking that will cover some 22 acres of the plant property with over 30-foot tall buildings, each some 90,000 square feet.

The BESS is part of an overall strategy to bolster the use of renewable energy sources — solar and wind — to help match up the timing of the production of energy with peaks in demand.

The BESS permit application is currently under review by the City’s Community Development Department, and once it’s deemed “complete,” the permitting process would begin, including an intensive environmental impact study and more.

The issue of the stacks came into sharper focus with a memorandum of understanding (MOU) the City signed with Vistra this past June that calls for the power plant building and stacks to be removed at Vistra’s expense by the end of 2027, or they must pay the City $3 million. The City has until the end of 2022 to decide if it wants Vistra to leave the trio of 450-foot tall stacks standing. The City Council decided to ask the residents what they want to happen.

The MOU also ended an eminent domain lawsuit the City filed to force Vistra to grant a utility easement through the plant property—running from the Front Street parking lot where sewer Lift Station No. 2 is located to Main Street and a space for injection wells to recycle the City’s wastewater.

It’s all part of the City’s Water Reclamation Facility (WRF) project under construction now. In the settlement, the City agreed to pay Vistra some $200,000 for the easements and to support the BESS project if it passes permitting.

City Manager Scott Collins said they’d received about 40 emails regarding people’s feelings about the stacks, prompting the meeting to discuss the matter.

Morrow explained that the company has “a lot of power plants,” using natural gas, nuclear, coal, and solar, and was now building BESS projects, including a 300 MW one at the Moss Landing Power Plant.

She said the stacks were put in to vent exhaust from the old power plant high into the air to disperse the boiler exhausts. But, with the plant shuttered since 2014, “They serve no purpose,” Morrow said. She added that the Federal Aviation Administration requires the blinking red lights on each stack always to be maintained “to prevent aircraft from colliding” with them. Those seemingly little red lights are actually 6-feet tall.

Vistra is required to inspect the stacks every year and report to the APCD on any contaminants that could become airborne. If the stacks are well maintained, she said they could last another 100 years (the first stack dates back to the mid-1950s and the other two the early ‘60s).

She said every 2-5 years; they must complete visual inspections of the stacks for structural integrity, which means climbing them and looking for cracks and other flaws. She said if they stay up, a “cap” will need to be placed on them to protect the interiors, which she estimated could cost $250,000 each ($750,000 total).

The caps would be custom-made and have to be lifted into place with a giant crane.

Vistra’s Tickner, an engineer, said so long as maintenance is kept up, “the structural integrity should remain good.”

Fuhs of the APCD said the stacks were last inspected for airborne materials in June, and all they found was some “rust and bird droppings,” and there was also very little asbestos in them.

DTSC’s Bystra said the agency has not done any investigations on the stacks but would get involved if they were found to have hazardous materials. DTSC has an active case going with regards to several areas on the plant property where there are known pollutants.

But the concentrations in both the soil and groundwater were small, and the DTSC is recommending they be left in place until the plant property is redeveloped.

If there are no hazardous materials in the stacks, Bystra said, the DTSC would not become involved.

The key question came from an audience member—Who has liability for maintenance if they remain?

Morrow said if the City chooses to keep them, then the City would be responsible for their maintenance and liability, as well as a future removal. That job has been estimated to be upwards of $5 million, in today’s costs, and possibly more in the future.

Morrow said the company’s stated intent is to remove the power plant and stacks. Vistra would then work with the City on possible redevelopment projects, which Morrow said were exciting.

Maruska put together an unofficial chart of what the possible costs to the City would be to keep the stacks, which he admitted was taken just from information he’d gleaned from the meeting.

It listed $250,000 per stack for the caps to make them safe; up to $50,000 a year for inspections; $10,000 a year for insurance if the stacks are not repurposed and an unknown amount if they are repurposed for something like an observation tower, a climbing wall, or bungee jumping. He also included a reserve fund of $2-$5 million for their future removal.

Having Vistra remove them would cost the City nothing.

For a City struggling to match tax revenues with expenses, the realization of costs seemed to take the air out of the room, even on a Zoom call.

The City plans to hold more hearings on the issue over the next year, in anticipation of the December 2022 deadline to give Vistra an answer—keep them or take them down.