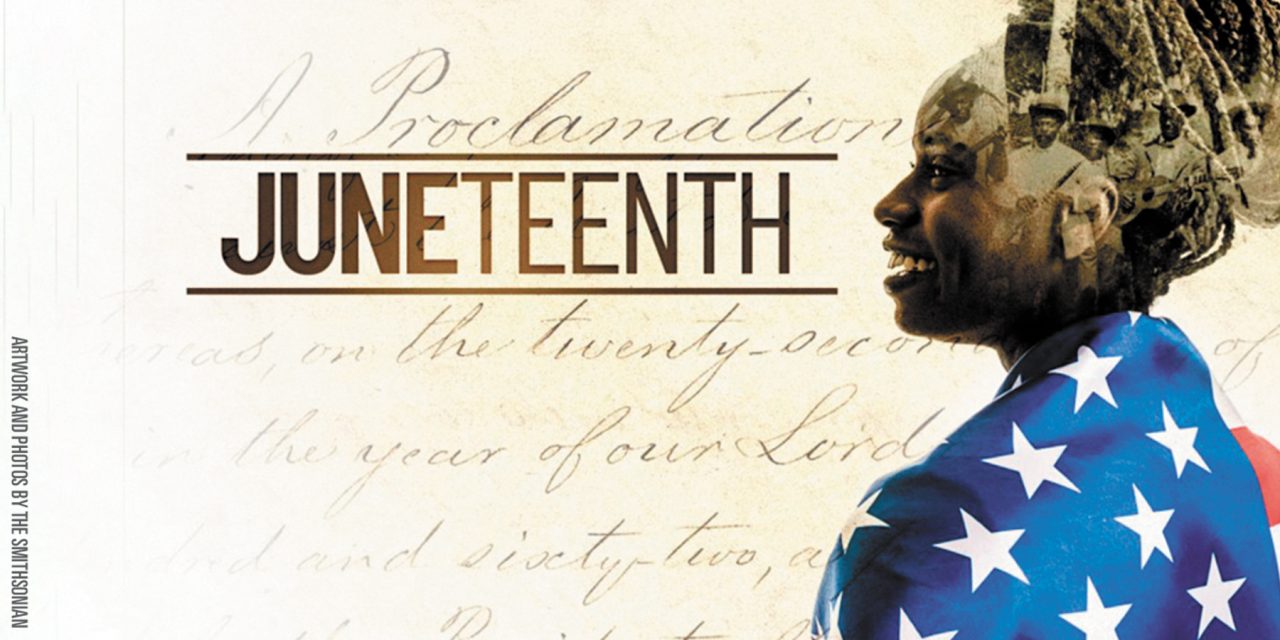

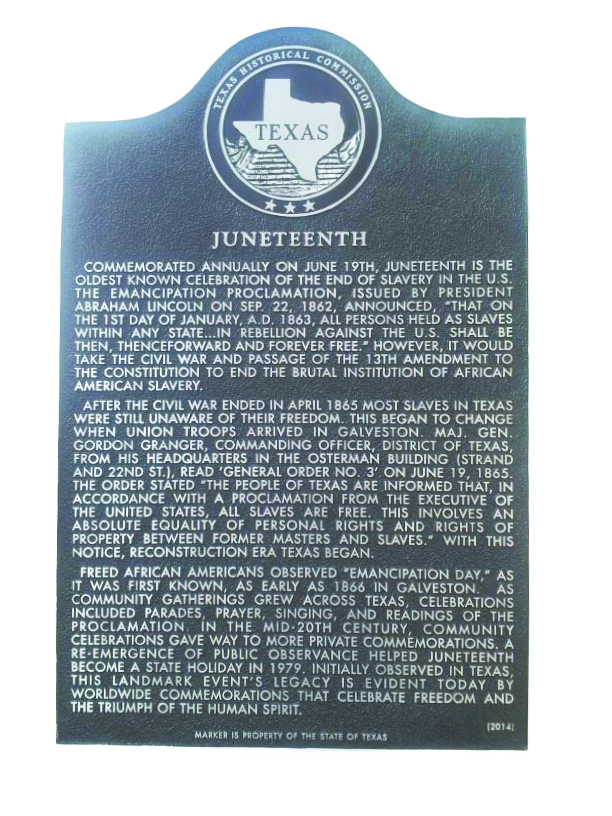

The warm month of June is home to a holiday that some say deserves much more national recognition and local celebration than it has received since it was first recognized. Juneteenth marks the final stop on June 19, 1865, of Union Maj. General Gordon Granger, arriving in Galveston, Texas, to announce, “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Abraham Lincoln was elected as the 16th president of the United States with a clear mandate to act in some way on the existence of state-sanctioned slavery—which violated both the inalienable human rights emblazoned in the Declaration of Independence and principles vested in the Bill of Rights. The conflict was inevitable, and the Civil War was a long and bloody war that cost 620,000 American lives on both sides of the battle.

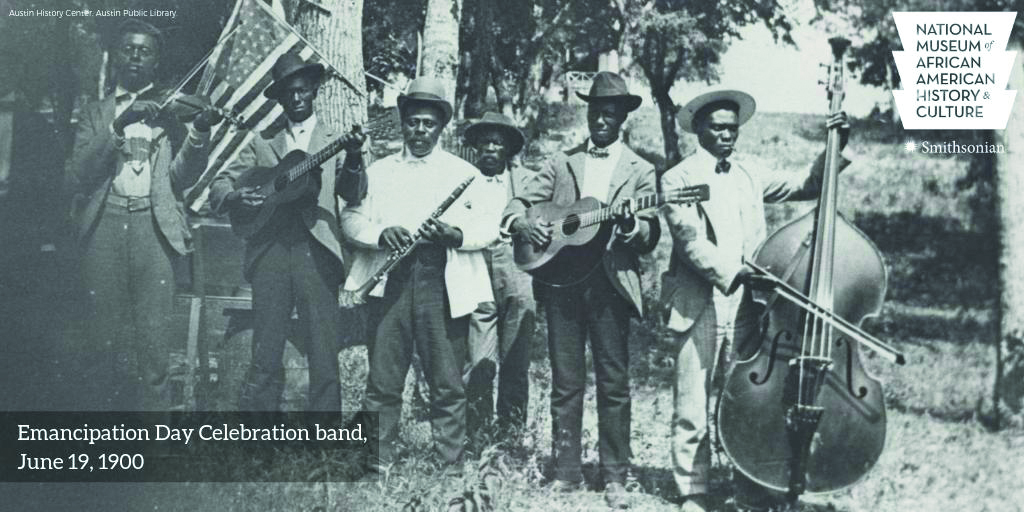

Juneteenth is the celebration of the June 1865 announcement in Galveston, Texas — little more than a month after the final battle of the Civil War, the Battle of Palmito Ranch on May 13, 1865.

Approximately 300 miles north, Maj. Gen. Granger rode into Galveston with his announcement less than 40 days later, and the day would live on as the marked day of celebration for the end of state-sanctioned slavery in the United States.

While the Emancipation Proclamation is far more famous, ringing the words of President Lincoln in the heart of the nation, it was Granger’s announcement that inspired the Juneteenth holiday.

According to the National Archives, “Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation, it captured the hearts and imagination of millions of Americans and fundamentally transformed the character of the war. After January 1, 1863, every advance of federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.”

With new vigor, Union soldiers battled against a ferocious Confederacy for two and a half years following Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.

Ironically, the Second Battle of Galveston also happened on January 1, 1863.

The Civil War waged on with 257 more battles in 29 months following the Emancipation Proclamation, according to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission.

The end of the Civil War came not with a bang, but a whimper, as 800 soldiers on both sides fought the Battle of Palmito Ranch.

But the final battle was of little to-do, as the announcement by Maj. Gen. Granger was a proclamation of victory for the Union and the end of the practice of slavery in the United States.

The California legislature recognizes Juneteenth as the third Saturday of June, “Juneteenth National Freedom Day: A Day of Observance.”

Juneteenth stands as the day in history when the proclamation that “all slaves are free” was made in all corners of the nation.

While Juneteenth celebrations remain concentrated in the south, especially in Texas, where it has been celebrated for more than 150 years, the holiday remains culturally significant to all Americans as the announcement of the end of state-sanctioned slavery following the end of the most deadly war in American history.