The agency can now turn its attention to officially designating the sanctuary

A major milestone has been reached in efforts to establish a marine sanctuary off the Central Coast, and it looks like Point Buchon will be cut out of the protections along with Cayucos and Morro Bay due to the offshore wind (OSW) energy projects.

According to a news release dated Sept. 6 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the umbrella agency that oversees the National Marine Sanctuary program, it is now done with the exhaustive environmental review of the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary (CHNMS), and the agency can now turn its attention to officially designating the sanctuary and putting into place the management plan, advisory board and all the rest of the bureaucracy needed.

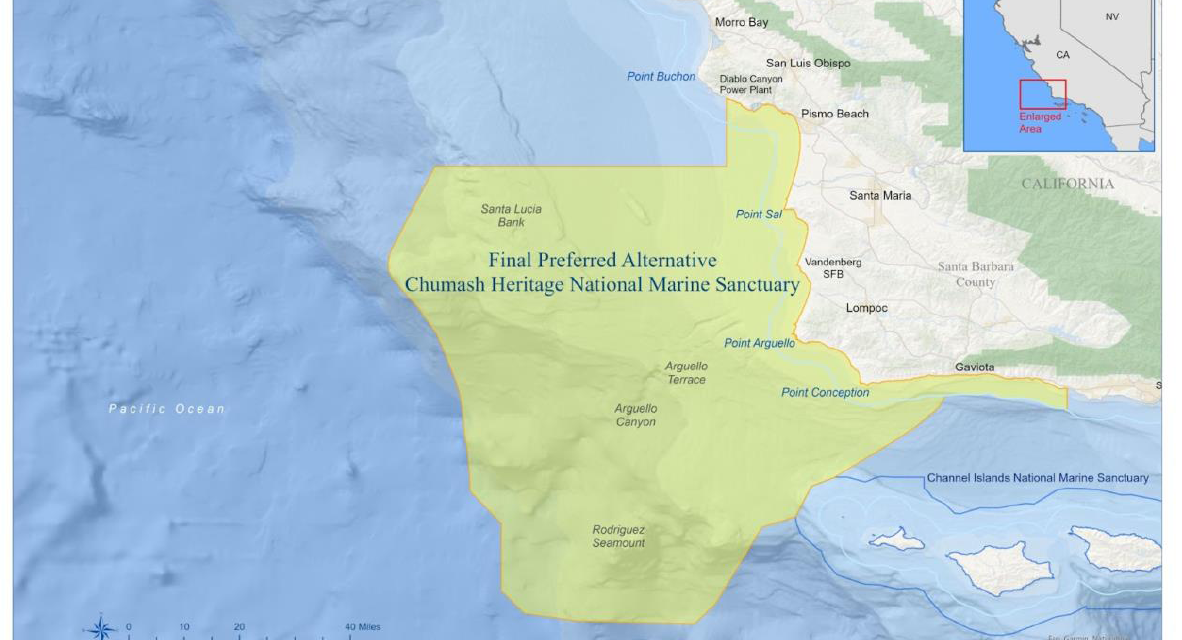

“Under NOAA’s preferred alternative,” reads the release, “the sanctuary would include 4,543 square miles of coastal and offshore waters along 116 miles of California’s Central Coast.” The sanctuary boundary spans from the beach out 60 miles and has maximum depths of 11,580 feet, over 2 miles deep.

At 4,543 square miles, it’s almost as large as Connecticut, which has a landmass of 4,842 square miles and is larger than Puerto Rico at 3,434.

According to NOAA’s official description, the new sanctuary’s northern boundary begins some 2 miles southeast of Diablo Canyon’s manmade marina and follows the shoreline to Gaviota Creek, which is south of Point Conception.

The sanctuary will stretch far offshore: “From Gaviota Creek,” NOAA said, “the boundary continues offshore to the southwest, and around Rodriguez Seamount and Arguello Canyon. From there, the boundary transits north consistent with Alternative 1 along the edge of Santa Lucia Bank to roughly the southern boundary of the Diablo Canyon Call Area.” That call area was another sizable patch of ocean offshore from Point Buchon and Diablo Canyon that had initially been proposed for an OSW project, but was dropped over concerns from the Navy’s Lemoore NAS, which uses the offshore areas for flight training.

“Upon designation, the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary would become the third largest national marine sanctuary in the National Marine Sanctuary System,” NOAA said.

It’s taken nearly a decade to reach this point in NOAA’s complicated process, and from the start, it’s focus has been to work with the many interested organizations each with their own interests, including tribes, indigenous peoples, community leaders, organizations, businesses, state and local officials, and even members of Congress.

The Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) “provides an evaluation of the expected environmental, social and economic effects of the proposed sanctuary, and reflects public input from multiple rounds of stakeholder engagement,” according to NOAA.

When the sanctuary is officially established, it would become the 17th in the National Marine Sanctuary System, NOAA said.

Native Americans, some of whom initially opposed the sanctuary, got this whole ball rolling, as it was Northern Chumash Tribal Council Chief Fred Collins, who along with local environmental groups, first petitioned NOAA to establish the sanctuary here and pay tribute to the Chumash.

“The sanctuary,” NOAA’s press release said, “would recognize and celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ connections to the region, and be managed with the active involvement of Tribes and Indigenous communities, inclusive of Indigenous values, knowledge and traditions.

“The sanctuary is anticipated to bring comprehensive community, and ecosystem-based management to nationally significant natural, historical, archeological and cultural resources — including kelp forests, rocky reefs, sandy beaches, underwater mountains and more than 200 shipwrecks.”

The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, which is the federally recognized Chumash Tribe and who owns the big casino resort in Santa Ynez, “will serve as a co-steward of the sanctuary.”

Chumash Chairman Kenneth Kahn said, “Every tribal nation across the country maintains a significant cultural tie to its aboriginal lands and waters. Sadly, for many, those connections have been difficult to reach. But today, with this announcement, the Chumash people take great strides in restoring our connection to our maritime history.”

Collins’ daughter, Violet Sage Walker, now Chairwoman of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council, was ecstatic. “This is a huge moment for the Chumash People and all who have tirelessly supported our campaign over the years,” she said. “My father, the late Chief Fred Collins, began the journey to protect these sacred waters 40 years ago, and we have been so proud to continue his work. I am delighted to celebrate his vision, today’s success, and the future of our people who will always be connected to past, present and future by this special stretch of coastline and the true magic its waters hold.”

The CHNMS will have another distinction — it will be the only sanctuary in the U.S. named after a people. All 16 others are named after the dominant geological feature of the area, hence Channel Islands, Farallon Islands, Monterey Bay and Olympic Coast NMS covering a large swath of Pacific Ocean on the West Coast.

The FEIS was published in two volumes and is available on the Marine Sanctuary program pages on NOAA’s website. See sanctuaries.noaa.gov/chumash-heritage to find the links to both volumes for download.

The document has a new surprise — expanded exclusion of a large chunk of SLO County coastline stretching from Cambria at the southern edge of the Monterey Bay NMS, south to below the Diablo Canyon Marina. That’s considerably farther south than the previous proposal that would have set the north boundary at Hazard’s Reef.

The CHNMS then spans all the way down to the Gaviota Coast in Santa Barbara County. It has some exclusion zones drawn in, in particular at Diablo Canyon and Port San Luis, as the Harbor District has interests in becoming a supply and maintenance port for the offshore wind companies.

And for the first time, NOAA fully admits that it cut that swath of coastline out at the request of the offshore wind energy companies who argued that their projects might not be economically feasible if they also had to go through a permitting process under the sanctuary act, on top of the exhaustive process already underway under the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management or BOEM.

“The reasons for further reducing the final sanctuary boundary at this time,” NOAA’s FEIS said, “center around clarifying information provided by the three Morro Bay Wind Energy Area leaseholders during the public comment period, and NOAA’s consideration of this information in light of renewable energy and conservation goals, the purposes and policies of the NMSA, and the purpose and need of the proposed sanctuary.”

“They also expressed,” NOAA continued, “concerns that existing sanctuary permitting procedures could jeopardize their ability to obtain financing for their development, and they sought to avoid the introduction of any permitting risk that NOAA might be unable in the future to approve one, several or all permit requests for cables in the sanctuary.”

Information on the OSW companies’ plans for the Morro Bay Call Area, a nearly 400-square-mile patch of ocean 20-30 miles off San Simeon, has been scarce but NOAA apparently has been better looped in at this point.

“In public comments, the leaseholders identified a need to develop between 15–24 subsea electrical transmission cables between offshore leases and two landing sites at Morro Bay and Diablo Canyon Power Plant (DCPP) grid connections. Presently they estimate landing roughly half of the cables at each grid connection.”

Those high-energy cables are expected to be buried in the seafloor and would run roughly 56 miles to Morro Bay and an additional 25 or so down to Diablo. As it is, any cables going to Diablo Canyon would have to avoid a Marine Protected Area off Montaña de Oro that was established over a decade ago under a state program.

The wind farms are also probably going to need a substation somewhere along that route and it remains to be seen where and how that would be done but a giant floating building wouldn’t mesh with the idea and the regulations of a protected sanctuary.

“The three leaseholders’ current design requirements,” NOAA’s FEIS said, “may mean they will seek access to a portion of the seabed between 30–45 miles wide, narrowing as cables approach land and shallower water. Their comments on the draft EIS note that subsea electrical transmission cables need broad gradual bends [rather than sharp turns] and need to cross other cables at largely 90-degree angles.”